The Unsolved Mystery of Father John Vraniak

John Vraniak's story begins like so many American immigrant tales of the early 1900s. Born in Slovakia in 1895 to Joseph and Johana Vraniak, he was part of a family that included four siblings: older brother Adolf and younger siblings Franco, Joseph, and Apolona. When John was just 12 years old, the family made the brave journey to America in 1907, eventually settling in West Pike Run, Pennsylvania, among a thriving community of Slovak immigrants.

What set John apart was his dedication to education and his calling to the priesthood. He attended St. Procopius College (now Benedictine University), an institution specifically founded to educate Czech and Slovak young men. John wasn't just a student there – he was an active contributor to campus life, serving as an editor for the college publication "Studentske Listy." One particularly intriguing detail is an article he published around 1916 with the roughly translated title "Roosevelt and the 'ape man' in theory." Written entirely in Slovak, its exact meaning remains a mystery, but it shows a young man engaged with the political and intellectual currents of his time.

By 1917, at just 22 years old, John had been appointed rector at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Virden, Illinois. This was no small responsibility for such a young priest, but by all accounts, he embraced it wholeheartedly. Those who knew him described him as cheerful, brilliant, and utterly devoted to his calling and his community.

A Beloved Community Leader

What strikes me most about John Vraniak is how he seemed to embody the best of what a community leader could be. Standing 5'6" and weighing about 150 pounds, he may have been slightly built physically, but his impact on Virden was enormous. He didn't just tend to his Catholic parishioners – he reached across denominational lines, earning respect from both Catholics and Protestants in the community.

John was a man of action who understood that faith needed to be lived out in practical ways. He organized a church baseball team called the Virden Slovaks, bringing sports and community spirit together. He purchased a Presbyterian church to convert into a parish hall, showing both his vision for community building and his ability to work across religious boundaries. These weren't the actions of a man planning to abandon his calling, which makes the police theory of voluntary disappearance seem particularly hollow.

The Fateful Day: March 5, 1923

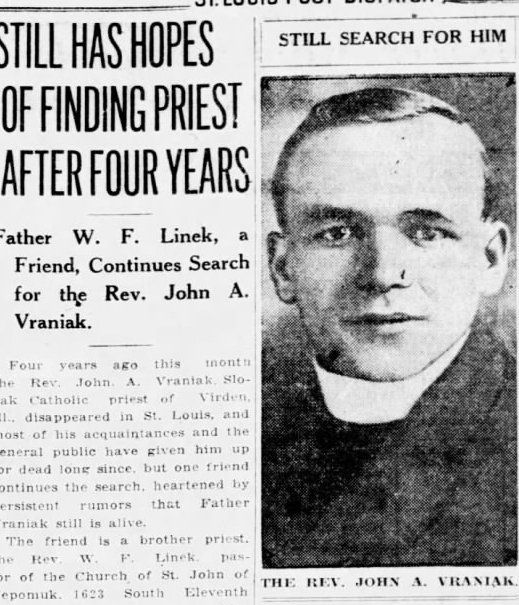

On what would be his final day, John's plans were completely ordinary. He needed to make the 85-mile journey to St. Louis to purchase items for an upcoming church bazaar – the kind of community event he was known for organizing. He also planned to invite his friend and fellow priest, Father V.F. Linek, to attend a church event. Linek served as pastor of Holy Trinity Slovak Catholic Church on Rutger Street in St. Louis, and the two priests had a friendship built on mutual support and shared heritage.

John's itinerary that day reads like a normal shopping trip. He stopped by Father Linek's home sometime before noon, but his friend wasn't there, so he left a message. He then went about his errands, purchasing items at Butler Brothers on 18th and Olive, and at Rice-Stix Dry Goods on 10th and Washington. Witnesses saw him at Butler Brothers as late as 2:30 p.m. His final planned stop was Mount Olive, Illinois, where he intended to invite another priest, Father Charles Knaparek, to the same church event.

This was clearly a man going about his normal business, thinking about his parish and upcoming community events. He had told his mother, who lived with him, to expect him back Monday night. There was nothing in his behavior that suggested a man planning to disappear.

The Discovery and the Search

At 12:15 a.m. on March 6, John's Buick coupe was found abandoned at Elm and Main Street in St. Louis's business district, near the Mississippi River. The tragic irony is that police initially didn't realize they were looking at evidence of a crime. They assumed the car had been abandoned by its owner and simply towed it to the police garage.

It wasn't until concerned parishioners from Virden traveled to St. Louis to report John missing that police began to understand the gravity of the situation. This detail always strikes me as particularly heartbreaking – a community so worried about their beloved priest that they made the journey themselves to raise the alarm.

The search that followed was extensive and gained national attention. John's disappearance appeared on front pages across the country, a testament to how unusual and concerning his vanishing was. Hospitals were searched in case he had been injured and was unable to identify himself. A garage owner in Venice, Illinois, claimed to have repaired John's car on Monday, and police found his account credible. Venice sits just outside St. Louis on the route between St. Louis and Virden, making this sighting plausible and adding another piece to the puzzle.

The Clues That Led Nowhere

The abandoned car held the only real clues to John's fate, and they painted a disturbing picture. Papers were scattered on the front seat, seemingly fallen from pockets during a struggle. Among them was a bill from the Catholic Art Association for rental of a film called "The Victim" – ironically, a movie about a priest searching for a murderer who had killed a poor family's father and thrown him off a bridge.

Most chilling of all was a phrase scratched into the paint of the back seat: "We won" in six-inch high letters. The car's undercarriage contained corn stalks and wheat, suggesting it had been driven through fields. John's St. Christopher medal had been pried off the door where he had attached it – a particularly cruel detail that suggests his attackers knew of its significance to him.

Theories and Dead Ends

The investigation produced several theories, each more troubling than the last. Police initially suggested John might have voluntarily left the priesthood, but Father Linek firmly disputed this, knowing John's character and dedication. Anonymous phone calls claimed he had been assaulted by "highwaymen" or used racial slurs to describe his attackers, but these seemed designed to misdirect rather than inform.

Perhaps most disturbingly, John's own brother Joseph claimed to have heard from him and said he was being held by an "organization," but couldn't provide details because police had asked him to stay quiet. Newspaper reports of this claim varied significantly, making it difficult to determine what Joseph actually said or whether he said anything at all.

The most credible theory centered on Andrew Rolando, a man with a documented hatred of Catholics who was already wanted for murdering another priest, Arthur Belknap. Rolando had supposedly been writing letters to a girl in Virden and may have visited the area. However, beyond his anti-Catholic sentiments and possible presence in the vicinity, there wasn't enough evidence to build a solid case.

A Community's Loss

The parishioners of Virden offered a $1,500 reward for information about John's whereabouts – equivalent to about $26,000 today. This wasn't just a token gesture; it represented a significant sum that showed how much the community valued their missing priest. Search parties combed the area between Virden and Venice, and there were plans to contact the Illinois attorney general for help with the investigation.

Why This Case Still Matters

A century later, Father John Vraniak's disappearance remains unsolved. What happened to this young priest who had dedicated his life to serving others? Was he the victim of a random crime, targeted because of his faith, or caught up in something more sinister? The scratched message "We won" suggests his disappearance may have been the result of some conflict or vendetta, but we may never know what that was.

What we do know is that John Vraniak was exactly the kind of person any community would be lucky to have. He bridged cultural and religious divides, organized community activities, and served his parishioners with apparent joy and dedication. His disappearance robbed not just his family and parish, but the broader community of someone who was making a genuine difference.

In our current era of true crime podcasts and cold case investigations, John Vraniak's story deserves to be remembered. While we may never solve the mystery of what happened to him on that March evening in 1923, we can ensure that his life and service aren't forgotten. Sometimes that's the best justice we can offer to those who vanished without a trace – making sure their stories continue to be told.