The Jonathan Coulom Case: A Twenty-Year Quest for Justice

On a cold, rainy night in April 2004, something terrible happened at a children's holiday camp in Saint-Brévin-les-Pins, a quiet seaside town in France's Loire-Atlantique region. When dawn broke on April 7th, counselors conducting their morning roll call discovered that one bed in the "Pouligen" dormitory lay empty. Ten-year-old Jonathan Coulom, known affectionately to his family as "Titi," "Jo," or "Cowboy," had vanished without a trace.

What began as a frantic search for a missing child would evolve into one of France's most perplexing cold cases, spanning two decades and crossing international borders. The investigation would eventually lead to Martin Ney, a German serial killer whose reign of terror had already claimed the lives of three German boys. But the path to justice has been anything but straightforward.

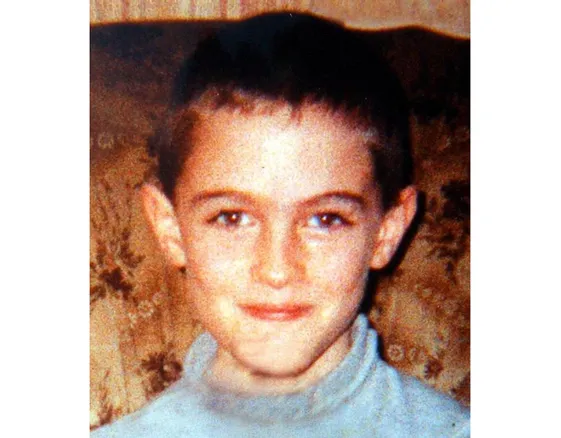

The Boy Who Loved Cowboys

Jonathan Coulom was a typical 10-year-old from the small town of Orval in the Cher department of central France. Living with his mother Virginie, stepfather Stéphane, and three sisters, Jonathan was part of a blended family held together by love rather than blood. His biological father had never acknowledged him, but Stéphane had stepped into that role when Jonathan was just eighteen months old, providing the stability and care the boy needed.

The family wasn't wealthy. Stéphane had worked as a cable installer until a workplace accident in September 2001 left him with a broken back, ending his career. Virginie had been a cashier until the birth of their youngest daughter. Despite their modest circumstances, they managed to provide for their children and were excited when Jonathan's CM2 class (equivalent to fifth grade) announced a week-long school trip to the seaside.

The holiday camp at Saint-Brévin-les-Pins represented a rare adventure for Jonathan. The facility was designed to give urban children from modest backgrounds a chance to experience the Atlantic coast, with its endless beaches and fresh sea air. For many of these children, including Jonathan, it was their first time away from home without their families.

A Night of Terror

The evening of April 6, 2004, had been festive at the holiday center. The children had enjoyed a party and settled into their dormitories around 11 p.m. Jonathan shared the "Pouligen" room with five other boys, sleeping peacefully after an exciting day by the sea. In a nearby building, young adults celebrating their BAFA completion (a French qualification for working with children) continued their own celebration until around 2 a.m.

The holiday center's security was minimal, reflecting the innocent times and the trust placed in such facilities. The dormitory doors had no handles on the inside, so for safety reasons, they were never completely closed when children were sleeping inside. A broken fence between the facility and the nearby road meant that access to the grounds was relatively easy for anyone determined to enter.

At midnight, during his final rounds, the supervisor checked on all the children and confirmed that Jonathan was in his bed, sleeping soundly. But sometime between that check and dawn, evil crept into the dormitory. When the bus driver who had transported the children to the center went to use the bathroom between 6 and 7 a.m., he discovered something alarming: the door to Jonathan's dormitory block was standing wide open.

The discovery of Jonathan's empty bed shortly after 7 a.m. triggered immediate panic. The boy had been wearing his pajamas when he went to sleep, and all his belongings remained neatly arranged in the room. There was no sign of struggle, no indication that Jonathan had voluntarily left his bed. On that cold, rainy night, no child would have ventured outside voluntarily, especially not in sleepwear.

A small detail would later take on enormous significance: investigators found a tiny patch of blood on the bedsheet where Jonathan had been sleeping. This physical evidence suggested that violence had occurred, though extensive DNA testing would eventually reveal the blood belonged to another child who had used the same bedding on a previous visit.

The Search Begins

Word of Jonathan's disappearance spread rapidly through the small community of Orval and beyond. His family was devastated, unable to comprehend how their beloved boy could simply vanish. The local gendarmerie launched an immediate investigation, treating the case with the urgency it deserved.

On April 16, 2004, the prosecutor of Saint-Nazaire officially opened a judicial investigation for kidnapping and false imprisonment. Catherine Salsac, an experienced lawyer, took on the representation of Jonathan's heartbroken parents. The legal machinery was in motion, but finding Jonathan remained the paramount concern.

The investigation initially focused on local suspects and possibilities. Investigators examined the backgrounds of known sex offenders in the region, conducted extensive interviews with camp staff and visitors, and appealed to the public for any information about suspicious activity on the night of April 6-7. Despite these efforts, leads remained frustratingly scarce.

The breakthrough moment that investigators had hoped for never came. Instead, on the evening of May 19, 2004, six weeks after Jonathan's disappearance, a terrible discovery was made at the Porte-Calon manor house in Guérande, approximately 30 kilometers from Saint-Brévin-les-Pins.

A Grim Discovery

The pond at the Porte-Calon manor was small and hidden from public view, nestled beneath the windows of the estate's tenants. It was not a location that a casual visitor would stumble upon. When Jonathan's body was found, the scene told a chilling story of calculated brutality.

The 10-year-old had been found naked, bound in a fetal position, and weighted down with a concrete block. His neck, wrists, and ankles were secured with nylon cord tied in precisely crafted marine knots, suggesting someone with nautical knowledge or experience. The careful positioning and the remote location of the pond indicated that whoever had done this possessed intimate knowledge of the local area.

The medical examiner's findings were both disturbing and puzzling. Jonathan had not drowned, nor did his body show signs of bone damage, visible injuries, strangulation, or toxic elements. The examiner concluded that the boy had likely died from suffocation or asphyxiation. The condition of the body, which had been in the water for weeks, made it impossible to determine whether sexual assault had occurred, though the circumstances strongly suggested a sexual motivation for the crime.

The discovery devastated Jonathan's family and shocked the broader French public. The methodical nature of the crime, combined with the tender age of the victim, generated intense media coverage and public outrage. Parents across France found themselves looking at their own children with new fear, wondering how such evil could exist.

International Connections

Just as French investigators were grappling with the evidence from Guérande, they received contact from an unexpected source. On April 22, 2004, investigators from Germany's Bundeskriminalamt (Federal Criminal Police Office) reached out to their French counterparts with startling information.

The German investigators had been tracking a serial offender who had been terrorizing children across northern Germany for over a decade. This perpetrator, dubbed "The Black Man," "The Masked Man," or "The Man with the Hood," had committed approximately 40 sexual assaults against boys in summer camps and children's homes. The killer was believed responsible for the murders of three German boys: 13-year-old Stefan Jahr in 1992, 8-year-old Dennis Rostel in 1995, and 11-year-old Dennis Klein in 2001.

The similarities between the German cases and Jonathan's murder were striking. All victims were young boys taken from institutional settings where children stayed away from home. The perpetrator demonstrated detailed knowledge of the facilities he targeted and showed a preference for locations near water where bodies could be disposed of. Most significantly, a witness reported seeing a sedan with German license plates parked near the Saint-Brévin-les-Pins holiday center on the night of Jonathan's disappearance.

Despite these compelling connections, the investigation into the German angle would remain frustratingly inconclusive for years. Without concrete evidence linking the crimes, French investigators continued to pursue other avenues, including the theory that a local predator might be responsible.

The Local Predator Theory

As the international investigation stalled, French authorities shifted their focus to a disturbing pattern that had emerged along the Atlantic coast. Between 1982 and 1998, a predator had been operating in approximately twelve holiday centers along the coast, primarily around Guérande, Saint-Brévin-les-Pins, and La Turballe.

This individual had sexually assaulted or attempted to assault at least 30 children, both boys and girls, aged between 7 and 13. The pattern of offenses suggested someone with intimate knowledge of the region's holiday facilities and their security weaknesses. The theory that a local resident might be responsible for Jonathan's murder gained traction, leading investigators to focus intensively on suspects within the region.

Extensive DNA sampling was conducted, with approximately 200 samples collected over five years. The investigation consumed enormous resources and manhours, but consistently failed to yield the breakthrough that would identify Jonathan's killer. The case gradually grew cold, leaving the boy's family without answers and the public without justice.

The Masked Man Revealed

The breakthrough in the German investigation came in April 2011, seven years after Jonathan's murder, through an unexpected source. A victim of childhood sexual abuse recognized a police sketch and identified his attacker as a man who had worked as a supervisor at a youth camp years earlier. This identification led German police to 40-year-old Martin Ney, a former educator living in Bremen.

Martin Ney, born on December 12, 1970, had built a career working with children, using his position to access vulnerable victims. When confronted by police, Ney confessed to the murders of Stefan Jahr, Dennis Rostel, and Dennis Klein, as well as approximately 40 cases of sexual abuse committed between 1992 and 2004.

The scope of Ney's crimes was staggering. He had operated across northern Germany, targeting children's homes, summer camps, and even private residences. His modus operandi was consistent: he wore dark clothing and masks to conceal his identity, earning him his sinister nicknames. He approached sleeping children in dormitories and homes, often touching multiple victims during a single incident before disappearing into the night.

Ney's confession provided crucial insights into his methodology and psychology. He admitted that he committed murder when he feared his victims might be able to identify him. The three German boys had died because Ney believed they posed a threat to his freedom and ability to continue offending. This calculated approach to murder demonstrated a level of premeditation and cold-bloodedness that chilled investigators.

However, when questioned about Jonathan Coulom, Ney denied any involvement. He also denied responsibility for the murder of Dutch boy Nicky Verstappen, another case with striking similarities to his confirmed crimes. Without additional evidence to link him to these international cases, German authorities could only investigate the crimes they could prove.

A Fellow Prisoner's Revelation

The case might have remained forever unsolved if not for the confession culture that sometimes develops in prison settings. In April 2018, 14 years after Jonathan's murder and seven years after Ney's conviction, a fellow inmate came forward with explosive information.

Markus (a pseudonym used to protect the witness) had spent several years in the same secure unit as Martin Ney at Celle prison in Lower Saxony. During their time together, the two men had developed what Markus described as a relationship of trust. In this environment, Ney allegedly made stunning admissions about crimes he had never been charged with.

According to Markus, Ney confessed to traveling to France and committing murder there. "He told me on several occasions that he abused a boy over there in France and that he killed him," Markus reported to German authorities in January 2017. The prisoner provided additional details that aligned disturbingly well with the known facts of Jonathan's case.

Markus described Ney's account of being spotted by "an older man with a dog" while in France, a detail that immediately resonated with French investigators who had a similar witness statement in their files. Even more specifically, Ney allegedly told his fellow prisoner that he had lost a brown leather backpack in France, one with "pockets as well as a lace on the top to close it," during a hurried escape from the crime scene.

The specificity of these details, combined with evidence that Ney had been in the Loire-Atlantique region in May 2004, gave French investigators new hope. A European arrest warrant was issued in October 2019, and in January 2021, Ney was extradited to France to face charges in connection with Jonathan's murder.

The French Investigation Intensifies

Upon his arrival in France, Martin Ney was charged with "murder of a minor under 15 years old" and "kidnapping, abduction, and arbitrary detention of minors under 15 years old." The charges reflected the serious nature of the crimes and the strong evidence that had accumulated over nearly two decades of investigation.

Under an agreement with German authorities, French investigators had eight months to build their case against Ney before he would be returned to Germany to serve his life sentence. This time pressure added urgency to an investigation that had already consumed countless hours and resources.

Judge Stéphane Lorentz led the French questioning of Ney, conducting extensive interviews designed to elicit admissions or uncover additional evidence. Despite the mounting circumstantial evidence and the testimony of his fellow prisoner, Ney maintained his innocence regarding Jonathan's murder. He consistently denied any involvement in the French case, just as he had denied responsibility for the Dutch murder case years earlier.

In March 2021, French investigators launched a public appeal for witnesses, hoping to find additional evidence of Ney's presence in France during the relevant time period. They specifically sought information about Ney's movements between 1990 and 2011, as well as any sightings of the distinctive brown leather backpack he allegedly lost during his escape.

Evidence and Methodology

The case against Martin Ney relies heavily on circumstantial evidence and pattern recognition rather than direct physical proof. Investigators have noted striking similarities between Jonathan's murder and Ney's confirmed crimes in Germany. The methodology showed consistent elements: targeting children in institutional settings, demonstrating detailed knowledge of the facilities, using restraints to control victims, and disposing of bodies in remote water locations.

The marine knots used to bind Jonathan suggested nautical knowledge, which aligned with Ney's background and the coastal location of many of his German crimes. The careful selection of the disposal site, hidden from casual observation but accessible to someone familiar with the area, indicated local knowledge that Ney could have acquired during previous visits to the region.

Physical evidence remained limited due to the time elapsed and the condition of Jonathan's body when discovered. However, the witness testimony about the German license plate, combined with Ney's alleged confessions to his fellow prisoner, created a compelling circumstantial case.

Crucially, German investigators discovered thousands of child sexual abuse images on Ney's computer equipment, demonstrating his ongoing obsession with young victims. While no images of Jonathan were found among these materials, the sheer volume of illegal content reinforced the picture of a predator with an insatiable appetite for victimizing children.

The Long Road to Justice

After eight months of investigation, Ney was returned to Germany in September 2021 to continue serving his life sentence. However, the French investigation was far from over. Prosecutors continued building their case, analyzing evidence, and preparing for what they hoped would be a successful prosecution.

In March 2024, twenty years after Jonathan's murder, French investigators announced that their investigation was complete. The evidence, while largely circumstantial, was deemed sufficient to proceed with prosecution. In September 2024, the prosecutor's office in Nantes formally requested that Ney be tried before an assize court for Jonathan's murder.

The request marked a significant milestone in the long quest for justice. In December 2024, this request was granted: Martin Ney was ordered to stand trial before the Loire-Atlantique assize court for the murder of Jonathan Coulom. However, Ney's legal team immediately filed an appeal against this decision, potentially delaying the trial further.

Impact on Families and Communities

The Jonathan Coulom case has left deep scars on all those affected. His family has endured twenty years of uncertainty, grief, and hope deferred. His mother Virginie, stepfather Stéphane, and sisters have lived with the constant pain of not knowing who killed their beloved boy and why.

The community of Orval has also been profoundly affected. On May 26, 2004, more than 1,000 people participated in a silent march through the town, demonstrating the profound impact Jonathan's death had on those who knew him and many who didn't. The case became a symbol of lost innocence and the vulnerability of children in seemingly safe environments.

For the broader French public, Jonathan's murder highlighted security concerns at children's facilities and sparked discussions about how to better protect young people during educational trips and holiday programs. The case influenced policies and procedures at similar institutions across the country.

Catherine Salsac, who has represented Jonathan's family throughout this long ordeal, has spoken about the family's enduring hope for justice. "Today, her client keeps the hope that the real culprit of Jonathan's murder will one day be tried before an assize court," she said, reflecting the determination that has sustained the family through two decades of waiting.

The Broader Context of Martin Ney's Crimes

Understanding the Jonathan Coulom case requires examining it within the broader context of Martin Ney's criminal career. His pattern of offending, which spanned more than a decade, reveals a methodical predator who continuously refined his approach to accessing and victimizing children.

Ney's psychological profile, developed during his German trial, painted a picture of a pedophile with a particularly dangerous combination of traits: intelligence, patience, access to victims through his professional role, and a willingness to kill to avoid identification. The psychological evaluation concluded that he represented a continuous threat with a high risk of reoffending.

The geographical scope of Ney's crimes, spanning Germany and potentially extending to France and other countries, reflects the international nature of many serial crimes in the modern era. His ability to travel freely within the European Union facilitated his criminal activities and complicated efforts to track his movements and connect crimes across national borders.

Questions That Remain

Despite the progress in the case, significant questions remain unanswered. The most fundamental question is whether Martin Ney is indeed responsible for Jonathan's murder or whether the actual perpetrator remains at large. While the circumstantial evidence is compelling, the lack of direct physical evidence means that reasonable doubt may persist.

If Ney is responsible, questions remain about how he selected the Saint-Brévin-les-Pins holiday center as a target, how he gained detailed knowledge of its layout and security weaknesses, and whether he had accomplices or local contacts who facilitated the crime.

The case also raises broader questions about the investigation of international crimes and the challenges of connecting evidence across national boundaries. The delay of over a decade between the crime and the serious investigation of Ney's potential involvement illustrates the difficulties inherent in such complex cases.

The Future of the Case

As of late 2024, the legal proceedings continue. While Ney has been ordered to stand trial, his appeal could delay the actual trial for months or even years. If the appeal is unsuccessful, he will face trial in France, potentially providing Jonathan's family with the answers and closure they have sought for two decades.

The trial, when it occurs, will likely focus heavily on the testimony of Ney's fellow prisoner and the circumstantial evidence linking him to the crime. The prosecution will need to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Ney was responsible, while the defense will likely challenge the reliability of jailhouse confessions and argue that the evidence is insufficient for conviction.

Regardless of the trial's outcome, the Jonathan Coulom case has already made significant contributions to understanding international criminal networks and the importance of cross-border cooperation in investigating serious crimes. The case has also highlighted the crucial role that witness testimony, even delayed by years, can play in solving cold cases.

A Legacy of Determination

Twenty years after that terrible night in Saint-Brévin-les-Pins, the Jonathan Coulom case continues to resonate as a testament to the persistence of those who refuse to let such crimes go unpunished. The investigation has survived changes in personnel, advances in technology, and shifts in public attention, sustained by the determination of Jonathan's family and the dedication of investigators who believe that every child deserves justice.

Whether Martin Ney ultimately faces conviction for Jonathan's murder or not, the case has demonstrated the importance of never giving up on cold cases. It has shown how international cooperation, new technologies, and the courage of witnesses can breathe life into investigations that seem hopelessly stalled.

For Jonathan's family, the upcoming trial represents both hope and anguish. After two decades of waiting, they may finally learn the truth about what happened to their beloved boy. Whatever that truth may be, they have shown remarkable strength in their refusal to let his memory fade or his case be forgotten.

The small boy from Orval who loved playing cowboy has become a symbol of the fight for justice that transcends national borders and persists across decades. In a world where such terrible crimes can seem overwhelming and unsolvable, the Jonathan Coulom case reminds us that dedication, cooperation, and hope can still prevail.

As the legal proceedings continue, one thing remains certain: Jonathan Coulom will not be forgotten, and those who loved him will never stop seeking the truth about the evil that took him away on that dark April night in 2004.

Sources

- Murder of Jonathan Coulom - Wikipedia

- German Serial Killer Charged Over French Cold Case - Courthouse News Service

- Martin Ney - Wikipedia

- Affaire Jonathan Coulom : le parquet demande un procès aux Assises - France 3

- Meurtre de Jonathan Coulom : l'Allemand suspecté renvoyé devant les Assises - France Bleu

- Affaire Jonathan Coulom — Wikipédia