A Father's Betrayal: The Disappearance of Curtis McCoy

November 18, 1989, was supposed to be a simple family outing in downtown Newark, New Jersey. Curtis Williams walked along the city streets with his girlfriend Sabetha Moore, their two baby daughters, and his two-year-old son Curtis McCoy, who was visiting from South Carolina for the Thanksgiving holiday. The little boy, wearing a green jacket, blue jeans, gray shirt, white tennis shoes, and his favorite blue Yankees cap, trailed a few steps behind the adults as they window-shopped through the downtown area. According to Williams, as the group approached an intersection, he reached behind to take his son's hand to help him cross the street. But when he extended his hand, he grasped only air. Curtis was gone.

In the moment, the story seemed plausible. A crowded city street, a small child lagging behind, a father's attention diverted for just a second. It happens. Children vanish in crowds. Strangers snatch toddlers from busy sidewalks. The initial investigation treated Curtis's disappearance as a non-family abduction, a kidnapping by a stranger who had seized an opportunity when a little boy fell behind his family. An extensive search was launched immediately. Police combed the area. Alerts went out across the region. But no trace of Curtis McCoy was ever found.

It would take seventeen years before the truth began to emerge. Curtis Williams had not lost his son in a crowded intersection. He had killed him. And for nearly two decades, he continued to profit from his son's death, claiming the dead child as a dependent on loan applications and tax returns, telling lies to investigators, and allowing Curtis's mother to suffer the unimaginable agony of not knowing what happened to her baby boy. Even when Williams finally confessed to the murder in 2007, even when he claimed to know where he had buried his son's body, Curtis McCoy was not found. He remains missing to this day, lost somewhere beneath the streets of New Jersey, a tiny victim of the person who should have protected him most.

Before the Disappearance

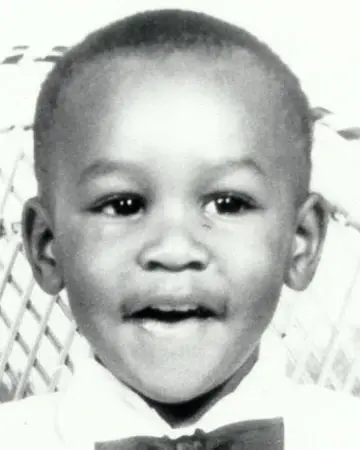

Curtis McCoy was born on October 6, 1987, to Lashawn McCoy in South Carolina. His mother had full custody of him, and they lived together in Gifford, South Carolina, where Lashawn was temporarily staying with her own mother. Curtis's father, Curtis Williams, lived in Union City, New Jersey, and maintained limited contact with his son. The relationship between Lashawn and Williams had ended, and Williams had moved on with Sabetha Moore, with whom he had two daughters.

At just over two years old, Curtis was a small child, standing between 20 and 24 inches tall and weighing approximately 25 pounds. He had black hair and brown eyes, a medium complexion, and two distinguishing marks on his back. Like most toddlers, he was energetic, curious, and entirely dependent on the adults in his life to keep him safe. According to his mother, Curtis did not want to make the trip to New Jersey for Thanksgiving 1989. Lashawn had to reassure him repeatedly that the visit would be fine, that he would be safe with his father, that he would have a good time. Her reassurances, tragically, would prove to be terribly wrong.

The last time Lashawn saw her son was in October 1989, about a month before his disappearance. When Williams asked to have Curtis visit for Thanksgiving, Lashawn agreed, trusting that her son's father would care for him during the holiday visit. She could not have imagined that she would never see Curtis again, that the little boy who didn't want to go to New Jersey had some instinct warning him away from danger, an instinct that went unheeded.

The Day Curtis Vanished

On November 18, 1989, Curtis Williams, Sabetha Moore, and their two infant daughters took little Curtis McCoy on what was described as a shopping trip through downtown Newark. The group was window-shopping, looking at storefronts and displays as they strolled through the city streets. Curtis walked slightly behind the adults, as small children often do, perhaps stopping to look at something that caught his eye, perhaps struggling to keep up with longer adult strides.

Williams's account of what happened next was dramatic and specific. As they approached an intersection and prepared to cross the street, Williams said he reached behind him to take Curtis's hand. The gesture was that of a responsible parent, ensuring a small child's safety before crossing a busy street. But when Williams reached back, his hand found nothing. Curtis was simply gone. Vanished. Disappeared into the crowd as if he had never been there at all.

The immediate response was exactly what one would expect when a child goes missing in a crowded urban area. Panic, confusion, a frantic search of the immediate vicinity. Had Curtis wandered into a store? Had he been distracted by something and stopped walking? Had someone taken him? Williams reported his son missing to the Newark Police Department, and an extensive search operation began. Police officers flooded the area, questioning witnesses, reviewing possible sighting locations, following up on any leads that emerged.

But the search yielded nothing. No witnesses came forward to say they had seen a small boy in a green jacket and blue Yankees cap wandering alone. No one had seen anyone leading a child away. No ransom demand arrived. No body was discovered. Curtis McCoy had simply vanished without a trace, as if the earth had opened up and swallowed him whole. The case quickly went cold, joining the tragic roster of missing children whose fates remain unknown.

A Mother's Desperate Search

For Lashawn McCoy, the disappearance of her son was the beginning of an unending nightmare. She had sent Curtis to New Jersey with his father, trusting that he would be safe, that he would return home after the Thanksgiving holiday with stories about his trip and memories of time spent with his father's family. Instead, she received a phone call telling her that Curtis was gone, that no one knew where he was or what had happened to him.

Lashawn's response demonstrated a mother's fierce determination. She didn't simply wait in South Carolina for news. She moved her entire family to New Jersey to be closer to the investigation, to be available to search, to refuse to let law enforcement forget about her missing son. She became an advocate for Curtis, keeping his case in the public eye, pushing investigators to keep looking, refusing to accept that her son might never be found.

As the years passed with no resolution, Lashawn continued to fight for answers. She knew her son. She knew that something about the story of his disappearance didn't add up. How does a child simply vanish from a busy street in broad daylight with no witnesses? How does a toddler evade an entire search operation? Where was Curtis?

In 2004, around the fifteenth anniversary of Curtis's disappearance, Lashawn reached out to Detective Keith Armstrong of the Jersey City Police Department major case unit. She asked him to take a fresh look at her son's case. She believed that Curtis Williams knew more than he was saying. She wanted investigators to dig deeper, to question the narrative that had been accepted for fifteen years. Detective Armstrong agreed to review the case, and what he found would finally begin to unravel Curtis Williams's lies.

The Fraud Charges

In September 2005, sixteen years after Curtis McCoy disappeared, Curtis Williams and Sabetha Moore were arrested and jailed on fraud charges. The charges were revealing and disturbing. Williams and Moore had allegedly stolen security deposits from prospective tenants of an apartment, a straightforward fraud scheme. But more significantly, they had falsely listed Curtis McCoy as a dependent on a loan application.

This second charge was the one that caught investigators' attention. Curtis Williams had been claiming his missing, presumably dead son as a dependent for years. He had been receiving financial benefits by pretending that Curtis was still alive, still part of his household, still his responsibility. The brazenness of the fraud was stunning. Williams had reported his son missing, had participated in the search efforts, had allowed an investigation to proceed based on the premise that Curtis might have been kidnapped by a stranger. All the while, he had been profiting from his son's disappearance.

The fraud charges gave investigators leverage. They could keep Williams in custody, could question him more aggressively, could build a case that went beyond financial crimes. Detective Armstrong's review of the case had already uncovered inconsistencies in Williams's story. The fraud charges suggested a man capable of exploiting his son's disappearance for personal gain. What else might Williams be capable of?

Investigators began to believe that Williams had not lost his son in a crowd. They began to suspect that Curtis McCoy had never left his father's custody alive, that the shopping trip story was an elaborate cover for something much darker. But suspicion is not evidence. They needed more.

Sabetha Moore's Testimony

The breakthrough in the case came from an unexpected source: Sabetha Moore herself. In January 2006, authorities opened a grand jury investigation into Curtis McCoy's disappearance. Williams was charged with his son's murder. The evidence that led to this charge came primarily from Moore's testimony. She told investigators that Curtis Williams had killed his son in November 1989 and then reported the boy as missing to cover up the crime.

Moore's allegations were explosive. If true, they meant that Curtis Williams had murdered his own toddler son and then staged an elaborate disappearance scenario to avoid detection. It meant that for sixteen years, Williams had lied to police, to his son's mother, and to everyone else while the body of a two-year-old lay buried somewhere, undiscovered and unmourned. It meant that the massive search operation, the years of investigation, the suffering of Curtis's family, had all been based on a carefully constructed fiction.

However, Moore's testimony had significant limitations. While she claimed that Williams had killed Curtis, she could not or would not provide crucial details. She did not know where Curtis's body was buried. She could not remember specific locations or provide evidence to corroborate her account. She claimed Williams had confessed the crime to her, but she had no physical evidence to support this claim. Her testimony alone, while damning, was not enough to guarantee a conviction for murder.

Prosecutors faced a difficult situation. They believed Moore was telling the truth. The fraud charges demonstrated Williams's willingness to exploit his son's death. The inconsistencies in his original story raised doubts about the stranger abduction narrative. But without a body, without physical evidence, without additional witnesses, the murder case was weak. Williams could potentially be acquitted at trial, and if that happened, double jeopardy would prevent him from ever being tried again, no matter what evidence might emerge later.

The Confession and the Plea Deal

Faced with these challenges, prosecutors made a controversial decision. They offered Curtis Williams a plea deal. In exchange for Williams revealing the location of his son's body and pleading guilty to hindering apprehension, the murder charges would be dropped. Williams would be sentenced to time served (he had been in custody since the fraud arrest in September 2005) plus five years of probation. He would walk free, having served less than two years for killing his son.

In May 2007, Curtis Williams accepted the deal. He admitted that he had killed Curtis McCoy in November 1989. According to Williams's confession, he had buried his son's clothed body in a shallow grave, approximately three feet deep, in a hilly, brushy area located underneath an elevated portion of the New Jersey Turnpike in Jersey City, New Jersey. He claimed the burial site was at an intersection beneath the highway.

Williams passed a polygraph test regarding the location of the burial site, which gave investigators confidence that he was telling the truth. They believed he genuinely knew where Curtis's body was and that he was providing accurate information. With this information, they could finally bring Curtis home. Lashawn McCoy could finally bury her son. The case could finally have some measure of closure.

But it was not to be. Despite Williams's detailed description and his passing the polygraph, despite extensive searches using machines, sifters, and shovels to excavate hundreds of square feet of ground beneath the New Jersey Turnpike, Curtis McCoy's remains were never found. Search teams combed the area Williams had described. New York State Police brought in specialized equipment. They dug through three feet of dirt and beyond, sifting through soil, looking for any trace of the tiny body that had been buried there eighteen years earlier.

Nothing was ever recovered. No bones, no clothing, no personal items, nothing that indicated a child had ever been buried in that location. Prosecutors believed that Williams had been truthful about the general location. Assistant Hudson County Prosecutor Debra Simon noted that after so many years, there might have been nothing left of the toddler's body. The New Jersey Turnpike area had undergone construction and changes over the eighteen years since Curtis's death. The burial site might have been disturbed during highway work. The body might have decomposed completely. The exact location Williams remembered might have been slightly off.

The Aftermath

True to the plea agreement, Curtis Williams was released from custody immediately after his sentencing in May 2007. He walked out of the courtroom a free man, having admitted to killing his two-year-old son and having served only the time he had already spent in jail on the fraud charges. Judge Peter Vazquez sentenced him to the maximum allowed for hindering apprehension: five years of probation. It was, by any measure, an extraordinarily lenient outcome for someone who had confessed to murdering a toddler.

The plea deal was deeply controversial and sparked outrage among those who followed the case. Lashawn McCoy was particularly vocal in her criticism. Her son's killer was free. She had no body to bury, no grave to visit, no final resting place where she could go to remember Curtis. The justice system had failed her in the most profound way possible. The deal had been predicated on Williams revealing where Curtis's body was, and even that limited goal had not been achieved.

Prosecutors defended the arrangement, though they acknowledged its imperfections. Debra Simon explained that the case against Williams was weak without a body. There were only two witnesses, Moore and possibly one other person, and both might have had ulterior motives to testify against Williams. Moore herself was facing fraud charges and might have been seeking to reduce her own sentence. The case was not a "slam dunk," Simon said. If they went to trial for murder and lost, they would have no leverage to make Williams reveal the burial location. And if they won, Williams would have no incentive to tell them where the body was.

The plea deal was designed to get information, Simon argued. It was better to have Williams admit to killing Curtis and provide a location, even if the body ultimately wasn't found, than to risk an acquittal that would leave Lashawn with nothing. Williams's lawyer, Jeffrey Jablonski, noted that knowing the location of the body was Williams's largest bargaining chip. The plea deal was the only leverage prosecutors had to get him to reveal that information.

The Unanswered Questions

More than three decades have passed since Curtis McCoy disappeared from a Newark street. His case remains officially classified as a non-family abduction by some agencies, even though his father confessed to killing him. This classification speaks to the strange limbo in which the case exists. Curtis's body has never been found. No physical evidence confirms Williams's confession. The only certainty is that a two-year-old child who went to visit his father for Thanksgiving in 1989 never came home.

Many questions remain unanswered. Why did Curtis Williams kill his son? What happened during that visit that led a father to murder his toddler? Was it a moment of rage, an accident that Williams panicked over and covered up? Was it premeditated, a decision made because Curtis was an inconvenience, a financial burden, a complication in Williams's life with his new girlfriend and their children? Williams never provided a motive for the killing. He admitted to the act but not to the why.

How reliable is Williams's confession? He passed a polygraph about the burial location, which suggests he believed he was telling the truth about where he buried Curtis. But the extensive searches found nothing. Did Williams misremember the exact location after eighteen years? Did construction on the New Jersey Turnpike disturb the grave? Was Curtis's body moved at some point, either by Williams or by someone else? Or was Williams lying about some aspects of his confession, perhaps to secure the plea deal while still concealing the true location of his son's body?

What role did Sabetha Moore play in Curtis's death? She testified that Williams killed the boy, but how did she know this? Was she present when Curtis died? Did she help dispose of the body? Did she simply know about it afterward? Moore was charged with fraud along with Williams, but the extent of her involvement in Curtis's death remains unclear. She claimed not to know where the body was buried, but this could have been a lie to distance herself from the crime.

A Mother's Unending Grief

For Lashawn McCoy, the lack of closure has been devastating. She fought for answers for fifteen years before Williams was even charged. She moved her family to New Jersey to stay close to the investigation. She pushed Detective Armstrong to reopen the case. She endured the agony of hoping her son was alive somewhere, only to learn that he had been dead all along, killed by his own father.

The 2007 confession should have brought some measure of peace. Finally, Lashawn knew what had happened to Curtis. Finally, she could stop wondering if he was alive somewhere, being raised by strangers, not knowing his real identity. Finally, she could grieve for her son as a definite loss rather than a terrible uncertainty.

But the lack of a body, the failure to recover Curtis's remains, meant that closure remained elusive. Lashawn has nowhere to go to be close to her son. She has no grave to tend, no place to leave flowers on Curtis's birthday or on Thanksgiving, the holiday he was supposed to be celebrating when he died. Curtis exists only in photographs and memories, forever two years old, forever wearing his blue Yankees cap, forever the little boy who didn't want to go to New Jersey because somehow, in a way he couldn't articulate, he knew it wasn't safe.

Lashawn has had to live with the knowledge that Curtis's killer received what amounts to a slap on the wrist. While she serves a life sentence of grief and loss, Curtis Williams served less than two years in custody and then walked free. The justice system valued information about a body's location more than it valued holding a killer accountable for murder. The calculus may have made sense from a prosecutorial standpoint, but from a mother's perspective, it was a betrayal.

Where Is Curtis McCoy?

This remains the central question of the case. Curtis Williams claimed he buried his son's body in a shallow grave beneath the New Jersey Turnpike in Jersey City. Extensive searches of the area found nothing. So where is Curtis McCoy?

One possibility is that Williams was truthful about the general location but imprecise about the exact spot. After eighteen years, memories fade. The landscape changes. What Williams remembered as a hilly, brushy area beneath the highway might have looked different in 2007 than it did in 1989. Construction projects, erosion, and natural changes could have altered the terrain. The grave might be close to where Williams indicated but not precisely where searchers looked.

Another possibility is that the body was disturbed at some point. The New Jersey Turnpike is one of the busiest highways in the country. The area beneath elevated portions of the highway might have been accessed for maintenance, construction, or utility work over the years. If workers unknowingly disturbed a shallow grave during one of these projects, Curtis's remains might have been removed and disposed of as debris, never identified as human remains.

A darker possibility is that Williams lied about the burial location. Perhaps he told prosecutors enough truth to pass the polygraph while still concealing the actual location of Curtis's body. This would give him the benefit of the plea deal while ensuring that Curtis would never be found, that physical evidence of his crime would never come to light. Without Curtis's remains, there would never be an autopsy that might reveal exactly how the boy died, whether there were injuries consistent with Williams's account or evidence of something worse.

It's also possible, as prosecutors suggested, that after more than thirty years, there is simply nothing left to find. A shallow grave, exposure to the elements, the decomposition process, all of these factors could have resulted in the complete disintegration of a small child's remains. Curtis might be there, beneath the turnpike, exactly where Williams said he was, but decomposed beyond the point where anything recognizable remains.

The Legacy of the Case

Curtis McCoy's case highlights several troubling aspects of the American justice system. The first is the difficulty of prosecuting murder cases without a body. While such prosecutions are possible and have been successful, they require substantial evidence beyond a confession. The absence of physical remains creates reasonable doubt. Juries struggle to convict without concrete proof that a death occurred. This reality gives perpetrators who successfully conceal their victims' bodies a significant advantage.

The case also demonstrates how financial crimes can sometimes provide the leverage needed to solve violent crimes. It was the fraud charges, Williams's exploitation of his dead son for financial gain, that gave investigators the opportunity to build a murder case. Without the fraud investigation, Williams might never have been charged with Curtis's death. This suggests that thorough investigation of all aspects of a suspect's behavior can yield unexpected pathways to justice.

The plea deal in Curtis's case remains controversial as an example of the compromises prosecutors sometimes must make. Is it better to secure a confession and some information, even if it means a killer receives a lenient sentence? Or is it more important to insist on accountability, even if that means potentially losing the case entirely and gaining no information at all? There is no easy answer. Prosecutors made the choice they felt gave Lashawn McCoy the best chance at some form of closure. Whether they were right remains a matter of debate.

Still Missing After 35 Years

Today, Curtis McCoy would be 37 years old. Age-progression images show what he might look like as an adult, though everyone involved in the case knows these images are merely exercises in imagination. Curtis never grew up. He never started school, never played Little League, never learned to ride a bike, never had a first date or a first job or any of the milestones that mark a life lived. He was two years old when his father killed him, and he remains forever two, forever missing, forever unfound.

The case stays active in databases of missing persons. Curtis's information remains on the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children website, even though he is not missing in the traditional sense. His father confessed to killing him. But without a body, Curtis is still officially missing. He is still being searched for, at least in theory. Tips are still accepted. Investigators would still follow up if new information emerged about the location of his remains.

For Lashawn McCoy, the search never ends. She will never stop hoping that somehow, someday, Curtis will be found. Maybe construction workers will uncover tiny bones. Maybe someone with information will finally come forward. Maybe Curtis Williams, on his deathbed, will tell the truth about where he really buried his son. Until that day comes, if it ever does, Lashawn lives with the permanent ache of a mother who lost her child and never got to say goodbye.

Curtis McCoy's story is a reminder that some cases never truly close. Some mysteries remain unsolved even when we know what happened. Some crimes escape full justice even when the perpetrator confesses. And some victims, especially the smallest and most vulnerable, remain lost forever despite everyone's best efforts to bring them home.

Somewhere beneath the streets of New Jersey, or perhaps in some other location entirely, the remains of a little boy in a green jacket and blue Yankees cap lie undiscovered. Curtis McCoy deserves better than this forgotten grave. He deserves to be found, to be returned to his mother, to finally rest in a place where he is honored and remembered. Until that happens, his case remains a painful reminder of a father's betrayal and a justice system's limitations, a two-year-old child lost in the cracks of a system that was supposed to protect him.

Sources

- The Charley Project: Curtis McCoy

- The Doe Network: Curtis McCoy

- New Jersey State Police Missing Persons: Curtis McCoy

- The Resource Center For Cold Case Missing Children's Cases: Curtis McCoy

- Philadelphia Inquirer: Man who admitted killing 2-year-old son is set free

- National Center for Missing and Exploited Children: Curtis McCoy

- M.I.A: The Missing Curtis McCoy

- News12: Jersey City police arrest victim's father in 1989 murder case